I am still under the effect of a rather random arrow of time when it comes to watching films. Mainly, this means that, since I am making up on new releases over time (when they are no longer new releases), I am at the mercy of certain momentous interests and fortuitous coincidences as to the time the films I am watching in a particular period were made. Well, sometimes it works for me, and other times not.

I remember many years ago, when I finally got to see the entire “Nixon” directed by Oliver Stone. There’s nothing particularly bad about this film, except that it’s almost a dry historical account of the most important events of his political career, obviously culminating with the famous Watergate scandal. In retrospect, it has a lot of good background information, and very little, if any, fictional element. But this richness in details makes this film good scaffolding if one wants to watch the amazing “Secret Honor” directed by Robert Altman. There is one heck of a close-up on a political character which will be difficult to be ever surpassed.

The two parts Jacques Rivette film “Joan the Maid” / “Jeanne la Pucelle” have this historical quality. We see the re-creation of the fifteenth century of a France at its lowest point during the 100 hundred year war. There’s little humor involved, the director limits himself to watch Joan (Sandrine Bonnaire) going through her adventure of freeing Orleans from the British troops and coronation of her king, then through her prison ordeals culminating with her being executing by burning on a stake for heresy. This is not quite a “period drama”, though. At least, if we are to compare this film to the late Eric Rohmer’s “Astrea and Celadon” , with which it has some similarities in style, we are focusing more on the legend, and in this case the legend is the character Joan, including her frequent contacts with the saints who inspire her in her deeds.

We do not see epic battles. Instead, we get to see a few people fighting here and there, winning some and losing some. Needless to say we don’t get to see any special effects. Everything is so concrete that you begin to wonder where God and the other saints in all that soup are. So yeah, we are mainly seeing the humans. Normal people, including the Dauphin and the haunted Joan, evolve or devolve throughout the film.

We get to see a less known side of Paris (the non French one, back then it belonged to Burgundy, a British ally) and the king’s humiliation, when he admits to have made a pact with Bourgogne. We also get to visit a castle where Joan is detained for a while and we even get a glimpse of the motivation that drives the castle’s seigneur to deliver her to England. Further, we get to witness the trial proceedings, which to me look like a rigged trial against a political dissident carried out in a communist country. We finally see what makes her abjure and then recant her abjuration, which leads her straight to the burning stake, with barely a communion granted at the last minute. Joan is sent to Heaven while the Holy Cross is shown to her from the sides.

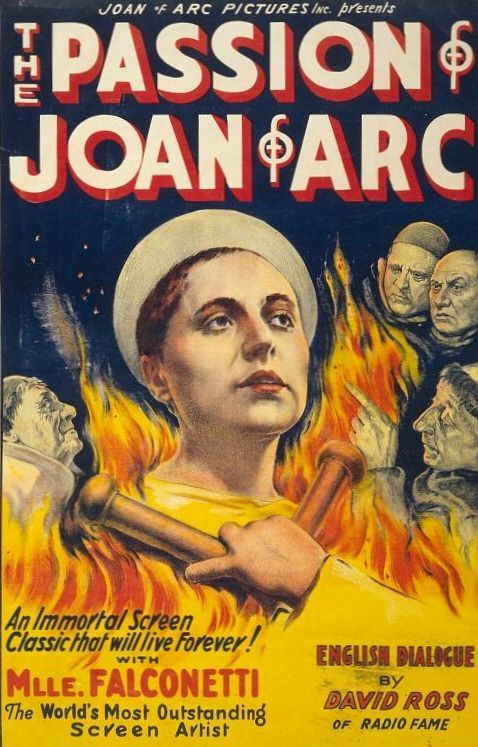

Yes, lots of good material here. Well, the natural question comes then: where’s the close-up? The answer regarding the close-up to a film made in the mid 90’s is in a film made in the late 20’s. Or it can be one of the answers, if you like this better. At least, this was what I saw in Carl Theodor Dreyer’s “Passion of Joan of Arc” .

Passion, that is, like the narratives of the lives of saints, containing the accounts of the ordeals they have gone through. It is worth mentioning that Joan of Arc, despite being excommunicated for heresy, was eventually beatified in the twentieth century, not long before this film was made. Starting from the records made by hand in the fifteenth century, Dreyer’s film focuses on her trial in Rouen, which is condensed to one day.

If one wonders what the charm of the old and perhaps silent films is, watching “The passion of Joan of Arc” can release much of the mystery, for it is a beautiful example of how emotion was expressed in film in a time when the talkie was nonexistent yet (there are a few late recreations of this fashion for communicating expressions, two titles come to mind: Mel Brooks’ “Silent movie” and Aki Kaurismaki’s “Juha” , both are “technically” silent films). We are given the chance to observe first-hand the emotional expressions of Joan, here played by Marie/Renee Falconetti. No, this time we do not have a pretty girl to watch. Instead, Joan’s face is everyone’s face, when dealing with accusations, schemes and betrayals, verbal abuses and she has little in control over what will happen to her. This is when we see her dressed like a man, with a male haircut, wide wondering eyes, freckles, tears and so on. She knows what she had seen, and remains undeterred by suggestions that she has in fact communicated with Satan. Even at the sight of the instruments of torture, she cannot understand why the heretic is her, and her torturers are in fact people of God. The only shed of light comes from the prison’s window, cross-shaped, which leaves on the floor a distinct shadow of the cross (yes, we can definitely recognize here what Lars von Trier had done with it in his “Epidemic”). But this cross is fading whenever the judges are stepping on it.

The illiterate girl falls into the trap of believing one priest as being the messenger of her king, but on the other hand she does not fall into other theological traps (“are you in a state of grace?”). But instead, she irritates her judges by telling that regardless of God liking or not the English, their fate is to leave France, except the ones who will die. Another sensitive aspect is her male outfit. She is even made to choose between remaining in this outfit (which by now we identify with her personal integrity and pride) and participating to the Catholic mass. A trick into a trick built into another trick.

Long story short, she can’t win. This actually means the fight is too uneven and the outcome has already been decided for her: the English want to make from her an example, so that the French will fear fighting against the English, due to the punishment associated with this. What she can do is choose between her death and her soul’s death. In other words, she can either sign a statement in which she abjures her stated heresies, or she will be excommunicated and executed. She takes the advice of some people in her court and she signs, but also marks a cross on the document, this meaning “I actually didn’t mean that”. Well, formally she has complied with the request, and instead of death, she gets the smaller sentence: life imprisonment and humiliation.

In Rivette’s version, her changing of mind is caused by the harsh treatments in prison, the French filmmaker is even staging a rape attempt. Here, Dreyer hints to an access of remorse when she gets the prisoners’ haircut: she is also stripped of her dignity. Realizing what she has done, she “abjures the previous abjuration” and ends up on the stake which was prepared for her long before that.

In the execution scene, carried out in Rouen, we get to know another character; the crowd. They are definitely aware of Joan’s ordeals, but they simply do not have the power to stop it. They are witnessing her death (beautifully shot), and realize she remained one of them, and the judged killed a saint. A public revolt ensues, but once again the city is ready for this, so the soldiers reply wielding chain maces against them and eventually kick them outside of the city walls.

This is where Joan’s legend will live on, and from where it will return with a vengeance. Now, Joan’s spirit is inseparable from the French popular spirit, and this is what (as we are suggested in the film) will ultimately change the war’s outcome.

This was my second incursion into Dreyer’s films, after viewing Ordet, and from this perspective I am not very competent to lead to the fine details. All can I see is that his films are growing into you, and will leave an indelible mark. Yes, Dreyer’s spirit is living into us, even without us knowing anything about it. This encounter is so rewarding…